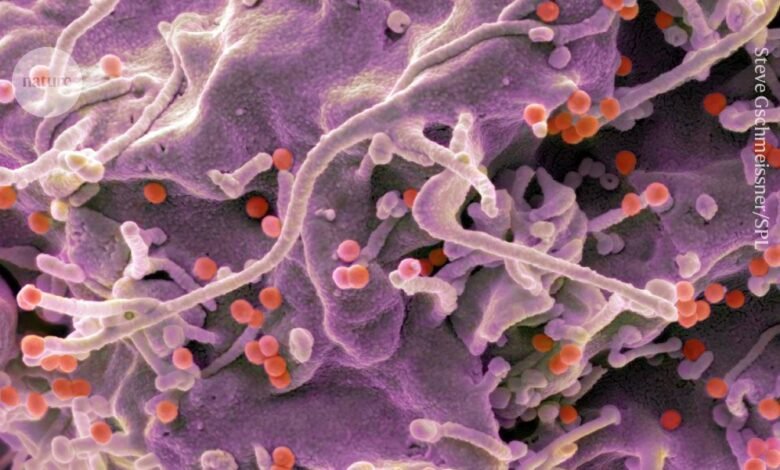

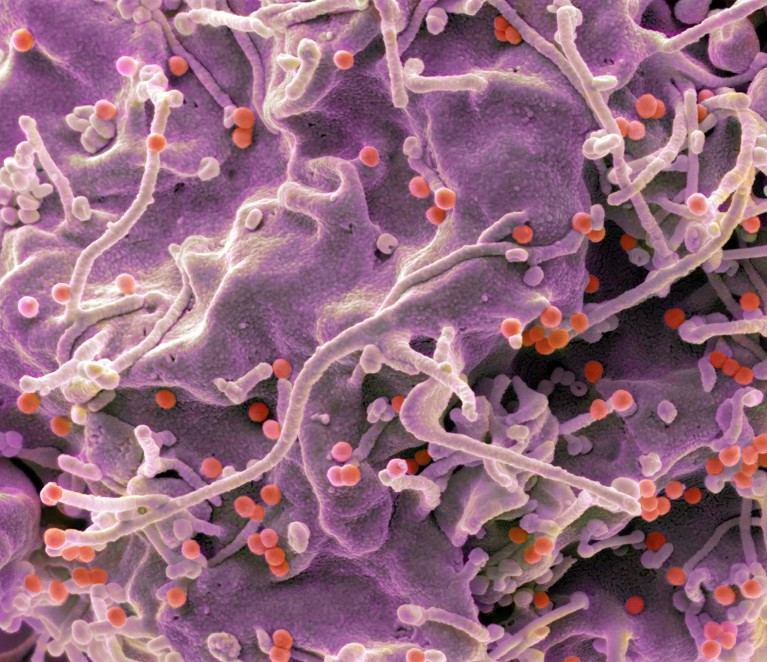

HIV particles (red dots) enter cells using proteins that bind to the cell membrane.Credit: Steve Gschmeissner/Science Photo Library

Two vaccine candidates using mRNA technology elicit a potent immune response against HIV, according to an early-stage clinical trial1.

The trial is only the third to test mRNA vaccines against HIV. “These are the first studies, so they’re very, very important,” says infectious-disease physician Sharon Lewin, who heads the Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity in Melbourne, Australia.

Around 41 million people globally live with HIV, for which there is currently no vaccine.

To design vaccines against a virus, researchers often study how the body clears the pathogen from its system, says Lewin. But HIV attacks the immune system, and the body rarely manages to clear it out. As a result, candidates for vaccines against the virus must undergo lots of testing through trial and error.

That makes HIV vaccines a good place to use mRNA technology. The first mRNA vaccine was approved in 2020, for COVID-19. Compared with other modes of delivery, mRNA vaccines can be modified at low cost quickly — in months, not years — which enables researchers to test out different strategies. The vaccines work by delivering instructions to cells, in the form of mRNA, to produce specific proteins typically found on the surface of viruses. This induces an immune response, which helps the body to recognize and clear out a virus should it be exposed to the real thing.

Bound or free

HIV uses an ‘envelope’ protein on its outer membrane to bind to and infect cells. In the latest study, published in Science Translational Medicine, a team including William Schief at Scripps Research in La Jolla, California, who works on protein design, conducted a small trial, comparing two vaccine approaches. In one, the standard method for HIV vaccine candidates, the cell is directed to produce envelope proteins that float freely. In the other, the mRNA vaccine instructs the cell to make envelope proteins that are attached to the cell membrane — similar to how they are found in the live virus. The authors describe animal tests of this method in a companion paper2.

The trial involved 108 healthy adults aged between 18 and 55 across ten study sites in the United States. It tested two membrane-bound vaccine candidates and one unbound candidate.

Participants each received three doses of a single vaccine, at a low or high dose, several weeks apart; which vaccine they received was selected randomly. The vaccines were provided by pharmaceutical company Moderna in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where Schief is vice-president for protein design.

Some 80% of the participants who received either of the vaccines that made membrane-bound proteins went on to produce antibodies that could block that protein from entering cells. By contrast, only 4% of the participants who received the unbound-protein vaccine produced corresponding antibodies.

“The difference is pretty striking,” says Lewin. She expects the findings to inform the development of future vaccine candidates.

Side effects

Source link