In early May, European politicians and university leaders gathered in Paris at Sorbonne University to deliver a message to US researchers affected by cuts made by the administration of US President Donald Trump: move here instead.

Ursula von der Leyen, the president of the European Commission, and French President Emmanuel Macron announced a 2-year funding package worth €500 million (US$571 million) to support researchers who want to move to the continent, as part of a scheme named Choose Europe.

Although von der Leyen didn’t name the United States or its president explicitly at the 5 May gathering, she said that parts of the world were questioning “free and open research”, describing that attitude as a “gigantic miscalculation”.

In April, the French government announced that money from the country’s €54-billion France 2030 strategic investment initiative had been set aside to fund international researchers who would like to work in France. Macron confirmed at the Sorbonne meeting that the separate €100-million cash boost would fund half of the costs of scientific projects involving international researchers moving to France.

US brain drain: the scientists seeking jobs abroad amid Trump’s assault on research

These announcements are the results of intense lobbying both in the French parliament and at the European level. A French-led conference, held in Brussels on 15 April and attended by French academic leaders and European policymakers, discussed issues around researcher mobility, partnerships and research programmes to help European scientific diplomacy get to grips with the changing global landscape.

Economist Jean-François Huchet, who is vice-president of France Universités, an association of higher-education organizations based in Paris and Brussels, hopes that coordinating the response at the European rather than country level will help to convince US researchers of Europe’s seriousness, and enable the region to accommodate more of those who want to move. On 19 March, a letter signed by research ministers from 13 European Union member states was sent to Ekaterina Zaharieva, the EU’s commissioner for startups, research and innovation. It asked for dedicated funding (subsequently granted by the €500 million for Choose Europe) and a dedicated immigration framework to “seize this historical moment”.

“All those researchers want to find a new country, a new possibility to continue their work. It’s really important for them to continue working. That’s the reason why I pushed with Commissioner Zaharieva to add [these funds] to Choose Europe. We want to help researchers coming from all parts of the world, especially the United States,” says Christophe Grudler, a French member of the European Parliament (MEP) who sits on the Committee on Industry, Research and Energy. Grudler initiated a separate lobbying letter that was sent on 24 March and addressed to both Zaharieva and von der Leyen.

“We can offer a lot of things: world-class universities, academic freedom, research ecosystems focused on excellence, and freedom and support to scientists,” he says.

Jānis Paiders, the deputy state secretary for the Ministry of Education and Science of Latvia, adds that his country was among those to endorse the 19 March letter “because academic freedom is under threat across the world”. He also notes there is “an ever-increasing need for Europe’s competitiveness as a whole”. Paiders calls for an “activity boom” to “welcome brilliant talents from abroad”, saying the policy aligns with both European and Latvian priorities.

Grudler’s 24 March letter, signed by 50 MEPs, stated: “In response to this crisis, the European Union must act swiftly to establish itself as a safe haven for these scientific talents. We have the tools and levers to do so, but we must accelerate and expand our response.” The letter also called for an accelerated visa strategy.

Push–pull effects

There is growing evidence that many US researchers are considering moving abroad. An analysis of Nature Careers jobs-board data showed that US applications for European vacancies increased by 32% in March, compared with the same month in 2024. And a self-selected poll of Nature readers in March found that 75% of respondents were keen to leave the country.

But some question whether these trends will manifest as a large-scale exodus of talent. For one thing, whereas early-career researchers might be mobile, senior academics, who are likely to be more attractive strategically for European policymakers, could find it harder to leave. “I would expect US politics to have the strongest effects on PhD applicants, finishing PhD students and postdocs. These people are not as deeply attached to the US academic system yet,” says Robert Basedow, who researches international political economics at the London School of Economics and Political Science.

US epidemiologist Scott Delaney is one academic who would struggle to leave. “I have two kids in grade school, ageing parents and a partner who loves her job here in the States.” Delaney runs a laboratory at the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and his National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant has been cancelled. “Relocating abroad would be a major disruption for all of them.”

On top of that, there is a big difference in the salary a scientist might expect in Europe compared with that in the United States. In France, for instance, a mid-career researcher might earn around €3,600 a month before taxes. A postdoctoral researcher at Stanford University in California, by contrast, would stand to earn the equivalent of around €6,000 a month, according to an analysis by The New York Times.

Trump gutted two landmark environmental reports — can researchers save them?

“It has to be a competitive situation to be able to attract researchers to come out” of the United States, says Thomas Kimbis, chief executive of the US National Postdoctoral Association in Bethesda, Maryland. However, he says, “it depends what happens over the coming months. I think the more time postdocs are sitting without a position, the more attractive just having a position, any position, becomes.”

There are differences, too, in expenses: Europe is generally cheaper to live in. “You have a huge difference in salary, but of course once you integrate the fees for US education, social security and health care, it’s not as big as the headline figure,” says Huchet.

And some think that any single fund won’t achieve large structural changes. “Although ultimately, top US universities have enormous funds, making it quite difficult for many European and other institutions to offer comparable salaries and research conditions, I do not think that a new EU fund can structurally change this situation,” adds Basedow. “Ironically, only Trump can do this, by taxing and eroding the funding and endowments of top US schools and thus undermining the material situation for academics in these places,” he concludes.

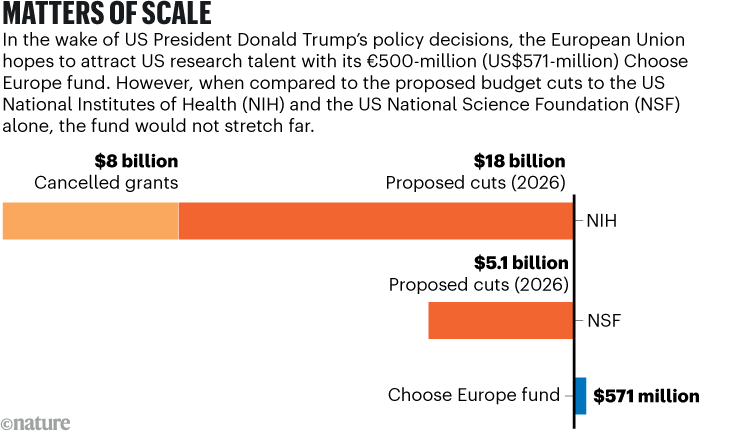

Choose Europe’s €500-million funding pledge is also dwarfed by the scale of the cuts the Trump administration is seeking — and has already made — to US science. In May, for example, it proposed cuts of around $5 billion to the country’s National Science Foundation (NSF) budget for 2026, and a $93-million cut to the NSF’s internal expenses. The NIH, the country’s main biomedical and public-health research funder, reportedly faces cuts of almost $18 billion next year. And the value of cancelled NIH grants already totals $8 billion (see ‘Matters of scale’). The EU’s research fund, Horizon Europe, is the largest pot of scientific funding in the world, with a budget of €93.5 billion to be spent until 2027.

Sources: Cancelled grants: Grant-watch.us (go.nature.com/4keqthj); NIH/NSF: Nature https://doi.org/prfr (2025)

“Half-a-billion euros and governments that don’t openly sneer at scientists sounds really attractive right now,” says Delaney. But, he adds, “While the €500-million investment is huge, it’s still only a fraction of what the US government spends on health research every year.”

Pan-European plans

Individual universities and organizations in the EU have also announced separate support packages to lure US researchers. In March, Aix-Marseille University in France announced a €15-million programme to attract researchers.

Its announcement was followed by one from the Free University of Brussels (VUB), which funded 12 postdoctoral positions. The Netherlands has also said it plans to open a fund to attract international researchers.

Spain has moved its international-competitiveness budget forward to spend more in this funding window, and is offering an additional €200,000 for each project for US researchers joining institutions in the country.

In April, the research council of Norway, the country’s main government research funder, pledged 100 million kroner (US$9.9 million) to attract researchers from abroad.

“This is a strategic opportunity that Europe wants to exploit and hopefully will be able to exploit,” says Marianne Riddervold, who researches transatlantic relations at the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs in Oslo.

Source link