As the electronic signals from our planet expand ever outwards into space, the world is marking 50 years since humanity broadcast its first radio message intended to get a response from the stars. No reply has been received, and none is expected for millennia, at least. But the form of this message, and others, raises questions about how humans see and portray ourselves — and about the legacies, scientific and otherwise, that any civilization leaves for others.

The radio message was transmitted on 16 November 1974 from the Arecibo Observatory in Puerto Rico, then the largest single-dish radio telescope in the world. It consisted of a series of binary digits, 0s and 1s, which represented numbers and pictures conveying basic information about humanity.

First came the numbers 1 to 10, and the atomic numbers of the elements that make up human DNA. Then came the formulae of chemical compounds that make up DNA nucleotides, the number of nucleotides in the human genome, and a depiction of DNA’s double-helix structure.

How would we know whether there is life on Earth? This bold experiment found out

The message also shared the height of the average US man (1.75 metres, or 5 foot 9 inches), a pixelated illustration of a human figure, and the size of the human population of Earth at that time (around 4 billion). Zooming out, it shared a diagram of the Solar System, indicating the message’s planet of origin, Earth. And, as a sign-off, came an image of the Arecibo radio telescope itself and the diameter of its dish (305 metres).

The message was aimed at the Great Globular Cluster in the constellation of Hercules, which is approximately 8 kiloparsecs away from Earth. This choice of target enabled many stars to be broadcast to at once, and was conveniently overhead at the time.

The message was sent, in part, as a stunt — the Arecibo telescope had just had a major upgrade, and astronomers wanted to showcase its capabilities. Radio astronomer Frank Drake, then director of the observatory, was tasked with commemorating what was essentially a new instrument.

Drake credits his administrative assistant, Jane Allen, with coming up with the idea of sending a message to extraterrestrial intelligence during the telescope’s dedication ceremony. And he set to work on designing the content of that message.

As he described in the book Is Anyone Out There? (1992), Drake put a lot of thought into how to represent humanity in the message. Technically, it was hard to do so using just 0s and 1s. The whole message of 1,679 bits was set out as a grid of 23 × 73 pixels, which is the only way to form a rectangle using those two prime numbers. Any entity receiving the message would need to work that out. If they did, the embedded visual pattern would be decoded.

Astronomer Frank Drake had a stained-glass window depicting the Arecibo message.Credit: Ramin Rahimian for The Washington Post/Getty

Drake wrestled with how to represent a human figure using so few pixels. He hoped to make it unisex, but that version “came out looking more like a gorilla than a human. So, I left it masculine rather than apelike.”

Thus, a picture of only half of humanity was broadcast from the Arecibo telescope. In hindsight, Drake admitted that he might have subconsciously tried to make it look a lot like himself — “as though I were beaming myself up Star Trek style”.

Diversity struggles

The Arecibo message demonstrates how the demographics of the scientists involved in the search for extraterrestrial intelligence (SETI) affected the character of the messages they sent. As with art, these messages are shaped by our biases, values and identities — mirrors that reflect our histories and cultures. If fields such as astronomy are dominated by a narrow demographic, as they were in the 1970s, then that will be reflected in the design and content of the messages, which might emphasize certain human experiences and perspectives over others.

It would be rash, however, to conclude that the burgeoning community of SETI scientists was unforgivably sexist. Drake, for one, was keenly aware of sensitivities around gender and other representations in extraterrestrial messages. He and other SETI pioneers, among them the astronomer Carl Sagan, were notable advocates for women.

How did the Big Bang get its name? Here’s the real story

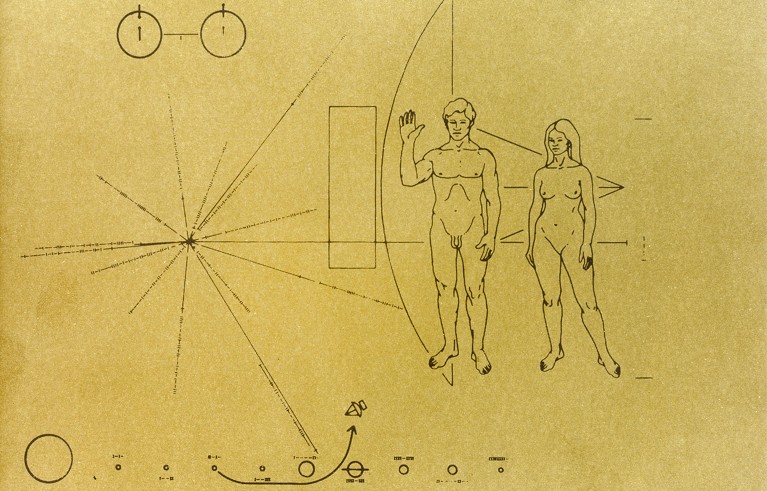

They had previously found themselves on similarly tricky territory. In 1972, Drake, Sagan and others helped to design a plaque that was launched on board NASA’s Pioneer 10 and 11 probes. Intended to serve as ambassadors to any intelligent life they might encounter, the Pioneer probes carried gold-plated aluminium plaques containing a message. Each plaque included a set of symbols designed to convey Earth’s location in the Galaxy, relative to a set of identifiable radio beacons — stars known as pulsars.

The plaques also displayed illustrations of two human beings: line drawings of a man and a woman, naked, standing side by side. The male figure is depicted waving, whereas the woman stands beside him, arms to her side.

The illustration was designed by Sagan and his then wife, Linda Salzman Sagan, who rendered the drawings. The Sagans wanted to generate an inclusive portrait of humanity, representative of all its members. In Cosmic Connection (1973), Sagan wrote that they tried to make the man and the woman look “panracial” by using ambiguous features such as wavy hair, no apparent skin colouring, and simply rendered facial features. The figures were also inspired by classical Greek imagery and statuary.

The Pioneer 10 and Pioneer 11 spacecraft launched in the 1970s with this plaque on board.Credit: GRANGER – Historical Picture Archive/Alamy

Despite these good intentions, the human images on the Pioneer plaques caused outrage on Earth. Feminist groups were angry. For one, the woman was a passive accompaniment to the man, who took the initiative to greet aliens with a wave. And while the depiction of the man was anatomically correct, the woman’s genitalia were conspicuously missing.

In his book, Sagan justified leaving out this detail on the basis that “conventional representation in Greek statuary omits it” and because of “our desire to see the message successfully launched on Pioneer 10”. By this, Sagan meant that there was concern at the time that the depiction of a culturally taboo feature might prevent the plaques from being approved by what he called NASA’s “scientific–political hierarchy”.

Sagan recalled how other groups were still repulsed by NASA sending what they perceived as ‘smut’ into space. One letter that he highlighted, to the editor of the Los Angeles Times, drew a comparison between the Pioneer plaque and pornography, and lamented that space-agency officials found it necessary to “spread this filth even beyond our own solar system”.

The nudity on the Pioneer plaque laid bare many points of cultural tension in the United States, ultimately highlighting differences instead of achieving the universal depiction of humanity that the Sagans sought to produce.

Pioneering women

Drake is generally credited with launching the field of SETI in 1960, using a radio telescope at the National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO) in Green Bank, West Virginia, to seek artificial signals coming from two nearby sun-like stars. Although none was found, this project, named Ozma, is considered the first scientific search for extraterrestrial life. The previous year, the observatory had begun to hire undergraduate students to work with scientists over the summer and conduct research projects. In the first year of the programme, the students were all male. In 1960, when he was planning Project Ozma, Drake was also tasked with hiring summer students, and decided to include women in the cohort.

In Is Anyone Out There?, Drake recorded that only 2 of the 12 students he admitted that year were women. But this was enough to evoke outrage on the part of others at the observatory. According to Drake, some of his colleagues thought that investing in female students was a waste of resources because they would eventually get married, become mothers and not contribute to astronomy. This was a common belief in the world of mid-twentieth-century physical sciences.

How AI is expanding art history

But Drake knew from experience that women could be excellent astronomers. His PhD thesis adviser at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, had been none other than Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin. She had been the first person to earn a PhD in astronomy from Radcliffe College — Harvard’s women-only institution, founded in 1879 — at a time when Harvard did not grant degrees to women. Later, she became the first woman in the university’s Faculty of Arts and Sciences to be promoted to full professor. Her research revealed that stars are composed mainly of hydrogen and helium, fundamentally shaping our understanding of astrophysics and the elemental composition of celestial bodies.

Drake persevered in admitting female summer students, and the first two, Ellen Gundermann and Margaret Hurley, came to work at the NRAO in 1960. Drake supervised them himself. Indeed, Gundermann and Hurley were the only other people in the control room when Project Ozma observations were conducted, and made history by assisting in the first search for extraterrestrial intelligence.

Gundermann would go on to complete a PhD in astronomy at Harvard and arguably became the first astronomer to detect a cosmic maser — an astrophysical phenomenon similar to a laser, but emitting microwave radiation rather than light, and typically found around black holes. In lay terms, Gundermann’s research provided key insights into how to observe and understand the farthest and most energetic parts of the universe. She would also become a mother, and her daughter, Jeanne Hardebeck, would earn a PhD from the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena and become an award-winning geophysicist.

But although scientists such as Drake did help to combat gender bias, at the same time they inevitably reproduced it, as the lone man in the Arecibo message bears out. This is not a condemnation of Drake. It is impossible to escape our cultural biases and, even when people attempt to embrace universality, they inevitably betray the markers of their limited perspectives.

Depicting ourselves

But these male-centric messages still offer us valuable perspectives. A more charitable interpretation of Drake’s choice to depict a figure resembling himself might see it as a form of artistic self-portraiture — a way, just as artists have done across history, to seek remembrance through the ages. Although pinpointing the origins of the self-portrait can be difficult (after all, prehistoric handprints in caves might have been a kind of self-portrait), Western art historians consider the genre a relatively recent fashion. Before the fifteenth century, appropriate images for portraiture were mainly religious, such as depictions of Jesus Christ or the Madonna. Generally, humans make self-portraits to communicate something of ourselves to others. It is a form of communication: ‘look at me, this is who I am’. People also create portraits to immortalize themselves, or at least a moment of themselves: an ‘I was here’ moment.

But when, in 1500, renaissance artist Albrecht Dürer created one of the first Western self portraits, he went a step further: it was not just about depicting himself, but also about referencing depictions of Christ at the same time. Replete with stylish golden curls, Dürer gazes straight at the viewer, his hands adopting gestures from early Christian iconography. In this form, he becomes both Dürer and Christ in one.

Albrecht Dürer’s 1500 self-portrait has religious overtones.Credit: GL Archive/Alamy

In Drake’s depiction of a human in the Arecibo message, he similarly universalizes himself simultaneously as ‘a man’ and as representing ‘mankind’ to the entire Universe. Drake and Dürer were both using the medium of self-portraiture to communicate their identity and transcend individuality, tapping into universal themes and symbols to connect with others on a deeper level. In doing so, they created artworks that serve as timeless reflections of humanity and its place in the cosmos.

In this view, the messages that humanity sends to extraterrestrial intelligences are not just scientific artefacts, but also works of art that reveal much about the people who created them. Whether consciously or subconsciously, these messages carry cultural assumptions and biases. They serve as a cosmic mirror, reflecting both our aspirations for universality and the limitations of our perspective.

Although it might be regretted that messages such as those in the Arecibo message and on the Pioneer plaques fail to represent the full scope of humanity, they do represent the complexity of the culture and people who sent them. Drake was a man who fought to uplift women and yet was constrained by the gender dynamics and norms of his time.

The 1970s was a period of immense cultural upheaval and change. Those who controlled and operated scientific infrastructure were overwhelmingly white men, and the remnants of their identities and the landscape of science can be seen in their messages. In this view, the messages humanity sends to the stars aren’t universal cosmic greetings. Instead, they’re bold reflections of who humans are, flaws and all, etched across the Universe for anyone, or anything, to see. And isn’t that much more interesting?

Source link