Leap Day only comes once every four years, including in 2024. But the reason we have it, including when we do and don’t, may surprise you.

Once every four years — well, almost every four years — our calendar gifts us with an extra day: February 29th, also known as Leap Day. Most of us who are born on this planet will experience perhaps around 20 such Leap Days in our lives, most a little less, some a little more, but its importance shouldn’t be underestimated. Leap Days, as rare and whimsical as they may seem, actually play a vital role in our role as timekeepers: they keep our annual calendar in line with the seasons, year-after-year and century-after-century. Although Leap Day might have a bizarre historical origin and is accompanied by a series of urban legends that surround it, its very existence is predicated upon scientific, not superstitious, reasons.

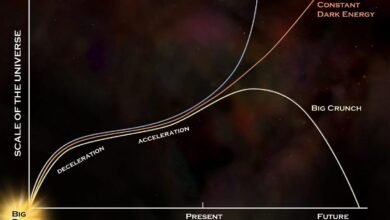

Without a Leap Day, the physics of planet Earth would quickly cause the seasons to move out-of-phase with our annual calendar, and the equinoxes and solstices would drift around the days, months and seasons. In fact, if we simply added a Leap Day to our calendars every four years without fail, things wouldn’t line up very well, either, which is precisely what happened for the centuries under which humanity followed the Julian calendar. Only if we properly account for our planet’s axial rotation and revolution around the Sun can we keep our calendar correct, and that’s what Leap Day is all about. Here are seven of the most bizarre, but still true, scientific facts that everyone should know.

1.) Our calendar requires them, in part, because a “day” isn’t 24 hours long. Think about how our calendar is structured: we divide the year, the period in which Earth’s seasons repeat, into days, where the Sun rises in the morning, sets in the evening, and then rises again the next day. Now think about our Solar System: the Earth, as one of the planets, rotates about its axis while it revolves around the Sun.

- The definition of a day, if we were to base it on the Solar System, would…

Source link