Debate about which guns actually “won the West” will probably go on indefinitely. The Colt, Winchester, Sharps, Springfield and other arms all have their advocates. But one firearm played a critical role in the West more than two centuries before Samuel Colt or Oliver Winchester saw the light of day. In the hands of Spanish frontiersmen—frontiersmen no less than Jim Bridger or Kit Carson—the comparatively primitive harquebus counterbalanced often overwhelming odds.

The vaunted Spanish expedition under Francisco Vásquez de Coronado that marched from New Spain (present-day Mexico) through parts of what today are Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, Oklahoma and Kansas between 1540 and ’42 left scant evidence of its passage, and for the next four decades Spanish colonial authorities showed little interest in the region. In 1580, however, Friar Agustín Rodríguez, a Franciscan lay brother eager to convert heathen souls to Christianity, convinced the powers that be that many such souls were waiting to be saved north of the existing mining settlements in New Spain. So, in the largest of the northernmost settlements, Santa Bárbara, Chihuahua, an expedition took shape. As a friar (or three, as it turned out) could hardly travel through hostile country alone, eight soldiers and a captain joined the party.

(Classic Image (Alamy Stock Photo))

For such a venture a detachment of nine soldiers was remarkably small. But its captain, Francisco Sánchez—nicknamed Chamuscado (“scorched”) for his flaming red beard—was a veteran of frontier service and knew his business. He made certain his men were well armed and well mounted, with a remuda of 90 horses at their disposal. For arms and armor the soldiers had harquebuses, swords, chain mail coats and breeches, and steel helmets. Armor also shielded their horses. Paramount were the harquebuses. Hernán Gallegos, who kept a journal of the expedition, wrote of a telling encounter with Indians soon after the party set out. “We fired quite a few harquebus shots,” he recalled, “at which the natives were very much frightened and said that they did not wish to quarrel with the Spaniards, but instead wanted to be our friends.”

Harquebuses of the late 16th century were of two basic types: the simple matchlock and the more advanced—albeit more complex and more expensive—wheellock. Writing in the early 1580s, Baltasar Obregón, another veteran of the frontier, offered this advice to explorers:

“Good harquebuses with supplies and duplicate parts should be carried. Most of them should be operated by fuse [match] because it often happens that the damp powder makes the firing of the flintlocks [wheellocks] difficult. Moreover, the harquebuses with fuses are easier to handle. The ones with flintlocks [wheellocks] often need a mechanic to make repairs and to replace the pieces that get out of order.”

In practiced hands a matchlock harquebus could fire two shots a minute. That wasn’t nearly as fast as a man could discharge arrows from a bow, but with six or eight armor-clad soldiers alternately loading and firing, harquebuses could be formidable weapons—or so the Spaniards hoped.

Chamuscado Heads North

On June 5, 1581, equipped with the requisite arms and armor, Chamuscado’s party—nine soldiers, three Franciscans (Friars Agustín, Francisco López and Juan de Santa María) and 19 Indian servants—rode north from Santa Bárbara, driving 600 head of stock before them. Descending the Río Conchos through rough country to its junction with the Río Grande (the site of present-day Presidio, Texas), they followed the latter northwest past the site of present-day El Paso. By August they had entered what today is central New Mexico and encountered the first of the multistory Indian pueblos. Such pueblos had no exterior doors at ground level. “The natives have ladders by means of which they climb to their quarters,” Gallegos observed. “These are movable wooden ladders, for when the Indians retire at night, they pull them up to protect themselves against enemies.” Meetings with the inhabitants proved peaceful, and the Spaniards were careful to keep things so.

In early September the party arrived at a cluster of pueblos along the Río Grande north of the site of present-day Albuquerque. Eager to return to New Spain with news of the expedition, Friar Juan set out alone from there on September 10, only to be killed by suspicious Indians. The party wouldn’t learn of his fate for weeks.

(National Park Service)

Moving on to San Marcos Pueblo (in the Galisteo Basin, south of the site of present-day Santa Fe), Chamuscado questioned its inhabitants about rumored mines and about wild cattle (buffalo), of which the party had heard mention since leaving the Río Conchos. Taking up handfuls of earth, the Indians pointed eastward and said such beasts were as numerous as the grains they held. Days later, after crossing the higher, pinyon-dotted country to the east, the Spaniards came to a river—the upper reaches of the Pecos. In the distance downriver rose a column of smoke. Perhaps recalling Obregón’s caution that Indians used smoke signals to warn one another, the party approached guardedly and, in Gallegos’ recollection, came upon “50 huts and tents made of hides with strong white flaps after the fashion of field tents. Here we were met by more than 400 warlike men armed with bows and arrows who asked us by means of signs what we wanted.”

Chamuscado and his men had come face to face with Plains Indians. Far outnumbered, they handled the situation with a proven tactic, as Gallegos recalled:

“We called the attention of all the Indians and then discharged a harquebus among them. They were terrified by the loud report and fell to the ground as if stunned.…We [then] asked them where the buffalo were, and they told us that there were large numbers two days farther on, as thick as grass on the plains.”

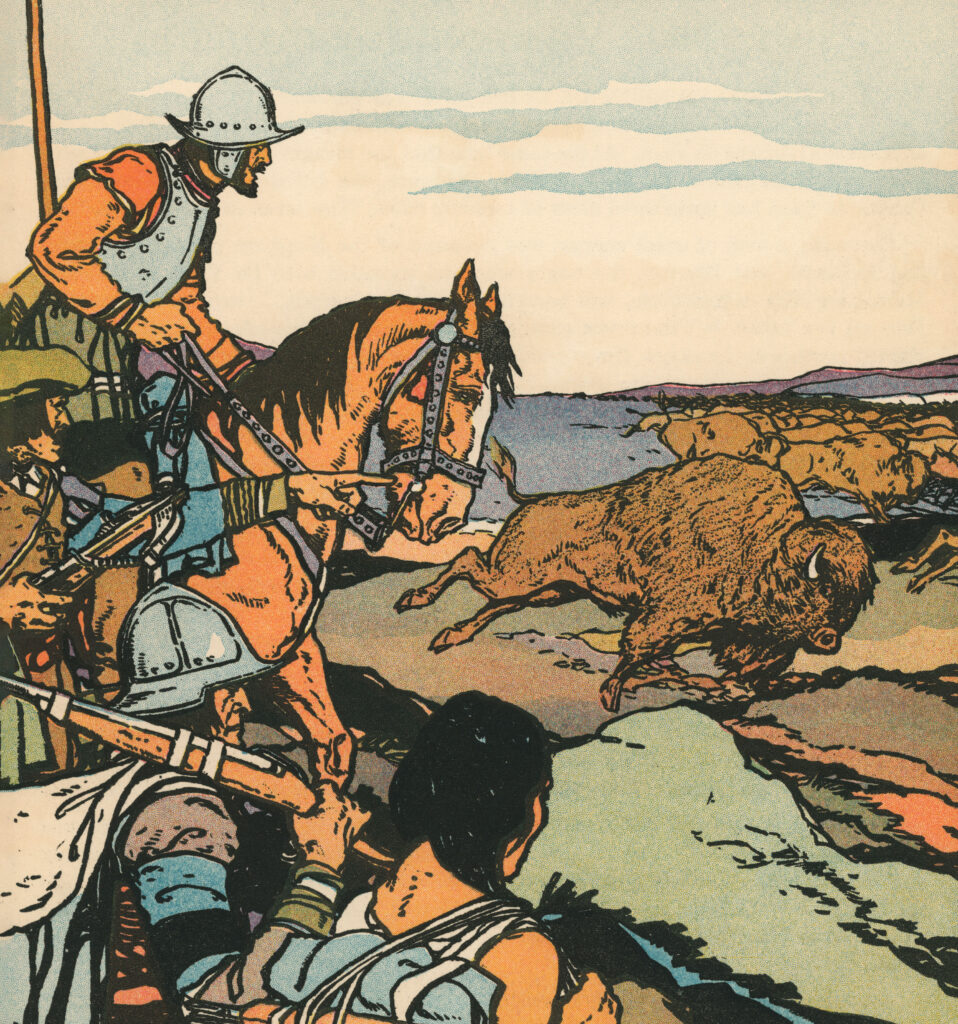

So, with an Indian guiding the way, they pressed on and soon encountered their quarry:

“At the water holes on the plains we found many buffalo, which roamed in great herds or droves of more than 500 head, both cows and bulls.…We killed 40 head with our harquebuses, to be used as food.…Indeed, it seemed as if the will of God had planned that no one should fire his harquebus at the cattle without felling one. This greatly astonished the guide who had led us to the said cattle. After leaving us, he told [others] of what he had seen us do.”

Around the campfire that evening the Spaniards agreed that efforts to find the buffalo had been well worth it. “Their meat is delicious,” Gallegos wrote, “and to our taste as palatable as that of our [beef] cattle.” They dried the remainder into jerky for the journey ahead.

For another week or two they explored the surrounding country, possibly reaching the headwaters of the Cimarron River. Finally, in mid-October they made their way back to San Marcos Pueblo. There they faced a challenge that called for a decisive response. “While we were at [San Marcos] some Indians from another settlement, which we named Malagón, killed three of our horses,” Gallegos recalled. Chamuscado promptly ordered five soldiers to saddle up and bring back the culprits, by force if necessary. When the soldiers reached Malagón, a pueblo of three to four stories with plazas and streets, they called out to its inhabitants, who had sought refuge on the rooftops, and asked who had killed the horses. When the Indians replied they had committed no such deed, the Spaniards again made a show of force, as recorded by Gallegos:

“We discharged the harquebuses to make the Indians think we were going to kill them, although we incurred great risk in doing so, for we were only five men facing the task of attacking 80 houses with more than a thousand inhabitants. When we had fired our harquebuses, the natives became frightened, went into their houses and stayed there.…We challenged them to come out of their pueblo into the open so that we might see how brave they were; [then] some hurled themselves from the corridors into the open in an attempt to escape, whereupon [two soldiers] rushed after them [on horseback], and each seized an Indian by the hair. The natives were very swift, but the horses overtook them.”

With the captives under their gun muzzles, the soldiers took them to San Marcos for punishment. The proposed penalty was grim indeed—public execution by beheading. Then one of the soldiers came up with an ingenious plan.

“It was agreed that at the time when the Indians were to be beheaded the friars should rush out to free them—tussle with us and snatch the victims away from us in order that the Indians should love their rescuers.…All was so done. At the moment when the soldiers were about to cut off the heads of the Indians, the friars came out in flowing robes and saved the captives from their perilous plight.”

(Graphica Artis (Getty Images))

The plan worked. On Indian assurances of the friars’ well-being, Chamuscado and his men then set out to explore more of the pueblo country, first riding west to fortresslike Acoma Pueblo, atop a mesa some 50 miles beyond the Río Grande valley. Rumors told of riches somewhere in the region, but time was running out due to the approach of winter. Finding no gold near Acoma, the soldiers pushed farther west, riding another 70 miles to Zuni Pueblo (in present-day west-central New Mexico). There they heard of yet more fabled mines and pueblos. But provisions were running low, and their supply of horseshoes was nearly exhausted.

So, amid falling snow, they turned back for the Río Grande. When they reached the pueblos and announced their intention to head home, Friars Agustín and Francisco demurred. After all, in their eyes the whole purpose of the expedition had been to convert lost souls. Thus, despite the since-discovered murder of Friar Juan, they insisted on remaining with the Indians. Reluctantly, Chamuscado agreed, and on the last day of January 1582, after setting aside tools and trade goods for the friars’ use, he and his men started south for New Spain.

The return trip down the Río Grande was no easy journey. “We were beset by many difficulties,” Gallegos recalled, “[and] we had to stand guard every night wearing armor.” Chamuscado fell ill to the point his men “decided to build a litter, which, slung between two horses, could take him quickly to Christian lands.” Having no tools, they had to cut the timber to construct a litter with their swords. Days later, despite their efforts, Chamuscado died. His men buried him—among the first of many graves Spaniards would dig along that trail in years to come. Finally, on April 15, 1582, the party straggled into Santa Bárbara, firing their harquebuses to alert townsfolk of their arrival.

Espejo’s Expedition

Among those who witnessed the homecoming of Chamuscado’s men was a prosperous cattle rancher from central New Spain named Antonio de Espejo—who, at the time, was hiding from the law. Months earlier, near Aguas Calientes, Antonio and brother Pedro had confronted two vaqueros for having shirked their labors during a roundup. Pedro had killed one of the men and wounded the other, whereupon local authorities had jailed him and imposed a heavy fine on Antonio. Unwilling to pay it, Antonio had slipped away and ridden north, reaching Santa Bárbara shortly before Chamuscado’s men. Espejo listened carefully as the soldiers described the region they had explored. He also noted grumbling from local Franciscans that two of their number had been left behind in pueblo country.

Like other adventurers who had found success in the New World, Espejo was intelligent, observant and willing to take risks. After weighing the circumstances, he proposed to organize, finance and lead an expedition north to “rescue” the Franciscans. With a willing friar and 15 soldiers—the latter armed and armored as Chamuscado’s party had been—Espejo left Santa Bárbara in November 1582. Accompanying the party were Indian servants, interpreters and a remuda of 115 horses and mules.

Down the Río Conchos they went, then up the Río Grande, retracing Chamuscado’s route. On reaching a point just south of the site of present-day El Paso, the horses were spent, so the men halted for a week to reshoe their mounts and craft stocks for their harquebuses. Diego Pérez de Luxán, who kept a journal of the entrada, described their gunsmithing work:

“[The Indians’] mode of fighting is with Turkish bows and arrows and bludgeons half a yard in length made of tornillo wood [screwbean mesquite], which is very strong and flexible. We all made stocks for our harquebuses from this tornillo because the wood was very suitable for the purpose.”

Their guns restocked and horses rested, the men pressed on. By mid-January 1583 they had entered future New Mexico in weather cold enough to freeze the water holes. Moving steadily north along the Río Grande, they halted in early February at a pueblo near the site of present-day La Joya and there received grim news. “The Indians told us by means of signs that the friars had been killed,” Luxán wrote, likely for the tools and trade goods Chamuscado had left with them. Girding for battle, Espejo and his men rode north to Puaray Pueblo (mistakenly referred to by expedition members as Puala, just north of the site of present-day Albuquerque), where the friars had been slain. It lay abandoned.

At that point Espejo could have, and perhaps should have, turned for home. En route, however, he’d heard the usual rumors about rich mines and resolved to seek them out. Breaking away from the Río Grande, the party headed northwest along the Jemez River and then turned west, passing Acoma Pueblo and riding through intermittent snowfalls. As the Spaniards rested their horses just beyond Zuni Pueblo, an Indian came into camp. The man, Obregón recalled, picked up a Spanish trumpet and “said that 60 days from his town toward the northwest was something shiny like that.” When pressed for specifics, the Indian said the people of that region wear the shiny metal on their arms and heads.

That was enough for Espejo’s men. Saddling up, they rode hard west. Days prior Zuni elders had assured them they would have no trouble, Obregón noted, as their harquebuses “shot fire and made the stones crumble like the lightning from heaven.”

There was no Indian trouble, at least initially, but their journey was long, and the country rugged. Just west of the Little Colorado River (near the site of present-day Winslow, Ariz.) the party negotiated a narrow, dangerous trail through a dense, rough woodland. “We descended a slope so steep and perilous,” Luxán recalled, “that a mule belongingto Captain Antonio de Espejo fell and was dashed to pieces.” Regardless, the Spaniards pressed on and finally found the mines “in a very rough sierra, and so worthless that we did not find in any of them a trace of silver, as they were copper mines and poor.” By then it was early May, and they had traveled some 260 miles west of the Río Grande.

So, they turned back, retracing their steps to Zuni by month’s end. At that point the party split, half the soldiers having agreed to escort the discouraged friar back to New Spain. Espejo and eight others continued east without incident until approaching a rancheria near Acoma. There real trouble started. “[The Indians] surprised us with a shower of arrows and much shouting,” Luxán recalled. “We rushed at once to the horses, firing our harquebuses. For this reason they wounded only one horse.”

The reason for the attack soon came to light. Days earlier one of Espejo’s men, Francisco Barreto, had “acquired” an unwilling Indian woman as a servant, and she had managed to slip away and forewarn her people. Determined to get her back, Barreto sought a parley with the attackers, offering to exchange other captive women. He asked Luxán to cover his back. As a gesture of good faith, Barreto left both his sword and harquebus on his saddle. He beseeched Luxán to do the same. Against his better judgment, Luxán laid down his arms and approached the Indians afoot with Barreto and the captive women.

Luxán’s misgivings were justified, as the group walked into another shower of arrows, two of which hit Barreto in the cheek and arm. In the confusion the captive women escaped. Meanwhile, Luxán and Barreto promptly retreated to their horses to recover their weapons. Considering the odds against them, the Spaniards decided it best to leave the field and continue toward the Río Grande.

(Library of Congress)

There more trouble awaited them, for Puaray Pueblo, the site of the friars’ murders, was no longer abandoned. As the Spaniards approached, some 30 Indians hurled insults at them from the rooftops. In no mood to negotiate, Espejo ordered an attack. “The corners of the pueblo were taken by four men,” Luxán recalled, “and four others with two servants began to seize those natives who showed themselves.” Placing their captives in a kiva, the Spaniards set fire to the pueblo. “At once we took out the prisoners, two at a time, and lined them up against some cottonwoods close to the pueblo of Puala [sic], where they were garroted and shot many times until they were dead. Sixteen were executed, not counting those who burned to death.”

With that murderous matter settled, the party continued east across the Río Grande, still on the lookout for mines. Food was getting scarce, so they halted at Pecos Pueblo to ask for provisions. But word had spread of their depredations at Puaray. When the terrified Indians at Pecos retreated to their rooftops, the Spaniards edged into the pueblo, Obregón recalled, “with much precaution and care [and] discharged some of the harquebuses while passing through the plaza and streets. When [the Indians] saw that they were so determined and well equipped with arms, they became so frightened that hardly one of them dared to appear.” Finally, an old man showed himself, begging the intruders “not to fire the harquebuses, nor to start fighting, because they wished to be their friends and would give everything they desired and needed.”

Thus reprovisioned, Espejo’s men turned south for New Spain, following the Pecos River. On Sept. 10, 1583, after 10 months on the trail, they arrived home. Espejo’s exaggerated account of the entrada made no mention of the disappointing mines or the 16 Indians executed at Puaray. But it did include a note that practically guaranteed other expeditions would follow:

“In the greater part of those provinces, there is an abundance of game beasts and birds.…There are also fine wooded mountains with trees of all kinds, salines and rivers containing a great variety of fish. Carts and wagons can be driven through most of this region; and there are good pastures for cattle as well as lands suitable for vegetables or grain crops, whether irrigated or depending on seasonal rains. There are many rich mines, too.”

Other expeditions did follow, one in 1590 and another in 1598, both larger and more heavily armed than Espejo’s. The era of the frontier firearm had begun.

For further reading on this topic author Garavaglia recommends The Rediscovery of New Mexico, 1580–1594 and Obregón’s History of 16th Century Explorations in Western America, both translated and edited by George Peter Hammond and Agapito Rey.