Perhaps no place is better to begin an adventure in the footsteps of Samuel “Champ” Ferguson—the most notorious of Confederate guerrilla leaders—than a small brewery near Sparta, Tenn., roughly 100 miles east of Nashville. One’s mind can become a little numbed when pondering Ferguson, who a 19th-century writer called a “thief, robber, counterfeiter, and murderer.”

Minutes after consuming the first of two Scorned Hooker IPAs at the eclectic Calfkiller Brewery, I meet my Ferguson guide, Craig Capps. He’s a 39-year-old Sparta resident, Tennessee law enforcement officer, U.S. Army veteran, part-time farmer, and ancestry.com aficionado.

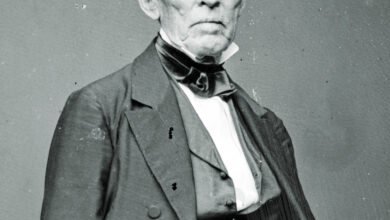

Capps is a distant relative of Ferguson, who the U.S. military hanged in Nashville for war crimes on October 20, 1865. He can also trace his ancestry to “Tinker Dave” Beaty—a Union guerrilla leader and Ferguson’s archenemy—as well as to Daniel Boone, Davy Crockett, and “Devil Anse” Hatfield of Hatfields and McCoys notoriety.

Funny how the world works.

(John Banks)

Born and reared in Tennessee, Capps is knowledgeable about the obscure Battle of Dug Hill, in which the villainous Ferguson played a central role. The “battle” was a skirmish, really, fought in the winter of 1864 by Ferguson and his guerrillas and a few Confederate regulars near the Calfkiller River, roughly 10 miles northeast of Sparta.

Alexander Fontaine Capps, Craig’s great-great-great-uncle—a guerrilla himself—fought under the man one of his 21st-century biographers called a “dim bulb.” John Alvern Capps—Alexander’s brother and Craig Capps’ great-great-great-grandfather—served in the 4th Tennessee Cavalry (CSA) and also fought at Dug Hill.

We plan to examine the unmarked battlefield out here in the rugged and sparsely populated area near Sparta. But first there’s a trip to Ferguson’s homestead site deep in the woods, less than a mile from the battlefield. Capps has secured permission for us to visit the private property.

Soon after departing the brewery, my guide parks his pickup on a muddy side road off two-lane Monterey Highway. For about 30 yards we walk along a red-clay trail—“good Tennessee dirt,” Capps says—and there it is.

No, not Ferguson’s homesite. Instead, we find an abandoned, circa-1920s mansion once owned by a wealthy doctor. Ivy creeps over its sandstone exterior. Wooden boards in the windows and front entrance prevent the curious like me from peering inside. Stephen King would smile.

“It’s haunted,” Capps says.

Nearby, Capps points out a large wild hog trap, a contraption I never deployed while growing up in suburban Pittsburgh. After a circuitous walk through the woods, we arrive at Ferguson’s homestead site, an unremarkable, flat piece of ground among cedars and beech near the Calfkiller River. No visible trace remains of the place where Ferguson lived with his wife and children.

It was here, shortly after the war, that the U.S. Army came for the notorious guerrilla leader, who had expected to be paroled. Instead, U.S. authorities put Ferguson under arrest in Nashville.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

Dark-skinned with curly black hair and black eyes, the Kentucky-born Ferguson weighed roughly 180 pounds, “without any surplus flesh.” A gambler, hard drinker, and a bully, he had a “tremendous voice” that could be “heard a long distance when in a rage”—which apparently was often. Ferguson had a rabid hatred for U.S. soldiers and enjoyed terrorizing Union sympathizers. Some say the hostility was fueled by the rape of his wife and daughter and death of his young son at the hands of Union soldiers, which Ferguson himself would deny occurred.

In all, Ferguson may have killed as many as 120 men—all self-defense or acts of war, he claimed. But in actuality, he murdered dozens. In cold blood, Ferguson shot and killed a man bedridden with measles—a former friend of Champ’s whom he suspected of visiting a Union recruiting center—while his five-month-old child lay in a crib nearby. In the aftermath of the First Battle of Saltville, Va., in early October 1864, Ferguson took out his wrath on captured White and Black soldiers alike, shooting some of them dead.

“We can’t judge those of the 19th century from the mindset of today,” Capps says. “But there’s no doubt Ferguson was a murderer.”

John Alvern Capps—Craig’s great-great-great-grandfather—and his brother, Alexander, testified at Ferguson’s trial in Nashville. Both witnessed killings by the dastardly guerrilla.

“They told the truth as they saw it,” Capps says of his ancestors.

While a brief drizzle offers a respite from the heat, Capps talks about the guerrilla war in White County and beyond. He has a condition I call the “1,000-yard Civil War stare”—a single-minded focus on everything associated with 1861-65. It’s endearing and not uncommon among us kindred souls.

“The war out here was truly brother versus brother, neighbor versus neighbor,” Capps says in a distinctive Upper Cumberland Appalachian twang.

Many families who lived in isolated towns in the Cumberland Plateau intermarried. Few here—several worlds away from the state capital in Nashville—owned slaves. Many simply wanted to be left alone but took up sides anyway. The war divided Ferguson’s family, too. His brother, James, served in the 1st Kentucky Cavalry (U.S.). In 1861, a Confederate sympathizer killed him.

Before visiting the Dug Hill battlefield site, Capps and I make our way to France Cemetery, where Ferguson’s remains lay beneath a comb grave. In 1909, an Oklahoma man claimed the guerrilla leader was alive, and, like similar stories about Lincoln assassin John Wilkes Booth, had somehow escaped justice. But my guide and I agree that’s poppycock.

(John Banks)

Although some believe the site is farther down the Monterey Highway, Capps believes the battlefield—our next stop—is less than a quarter-mile from the cemetery. Capps bases his conclusion on years of studying the fighting and hundreds of visits to the site. Decades ago, a local found battle relics here in the woods near our stop.

“Look how steep that is,” Capps says after our arrival. He points to a thickly wooded hillside of mostly beech and cedar. Behind and well below us flows the Calfkiller River.

At Dug Hill on February 22, 1864, from behind trees ideal for concealment, dozens of Ferguson’s guerrillas awaited two companies of 5th Tennessee Cavalry (U.S.). Fearing a surprise attack on his headquarters in Sparta, their colonel had sent 80–110 soldiers to rid the nearby woods of guerrillas.

Serving as the tip of the cavalry’s spear, John W. Clark—a private in the 1st Tennessee Mounted Infantry riding with the 5th Tennessee Cavalry—advanced up a narrow mountain road with two comrades. Then, about 100 yards away, Clark spotted two guerrillas astride their horses—bait to lure the cavalrymen into a trap.

“I sounded the double-quick charge signal, and lit out after them, and about the time the company caught up we spied two lines of battle formed,” Clark recalled years later. “One line was up to our right on high ground about 300 feet above us. We were in the Dug Hill road, which ranged around the mountain about 600 yards from where we entered it. At the loose end of a thin hill was another line of battle. By this time another line had formed behind us, and the johnnies were cross-firing on us three ways.”

Dozens of U.S. soldiers tumbled from their saddles.

“The smoke was so dense,” Clark remembered, “that you could not tell one man from the other.”

“One of the most ridiculous battles ever fought,” a Rebel fighter recalled.

(John Banks)

Some U.S. soldiers scrambled down the hillside to the Calfkiller River. One hid in a log until the battle had ended before making his way back to Sparta. Others surrendered to a Confederate officer, who passed them to the rear to Ferguson, “who shot them in cold blood,” according to a U.S. soldier. Some of the cavalrymen had their throats slit. Later, in a vacant storehouse, a local claimed to have examined the bodies of 41 U.S. Army dead—38 with bullet wounds in the head, three with crushed skulls. But the exact death toll is unknown. The guerrillas suffered far fewer casualties, if any. Months afterward, skeletons are said to have turned up by the road and in the woods.

Although unmarked and largely forgotten, the battle site holds a power over those of us who relish walking in the footsteps of long-ago soldiers. For Capps, a U.S. Army veteran, the place is surreal.

“When I learned my great-great-great-grandfather had fought here,” he tells me, “it was like a child going to Normandy with a D-Day veteran. If he had been killed here, I wouldn’t be here.”

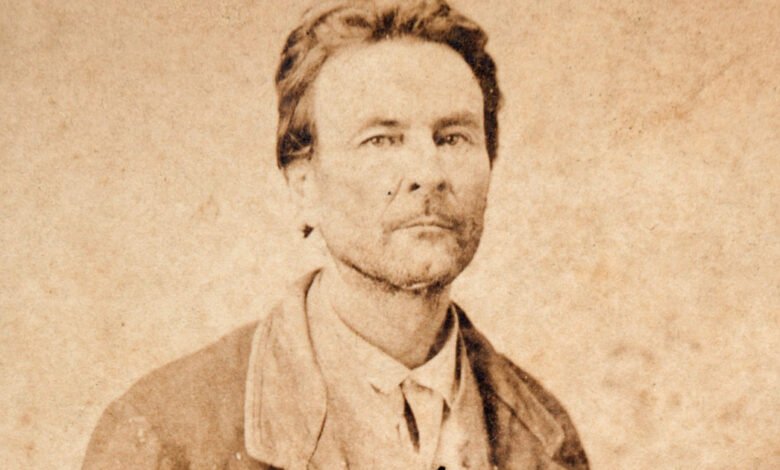

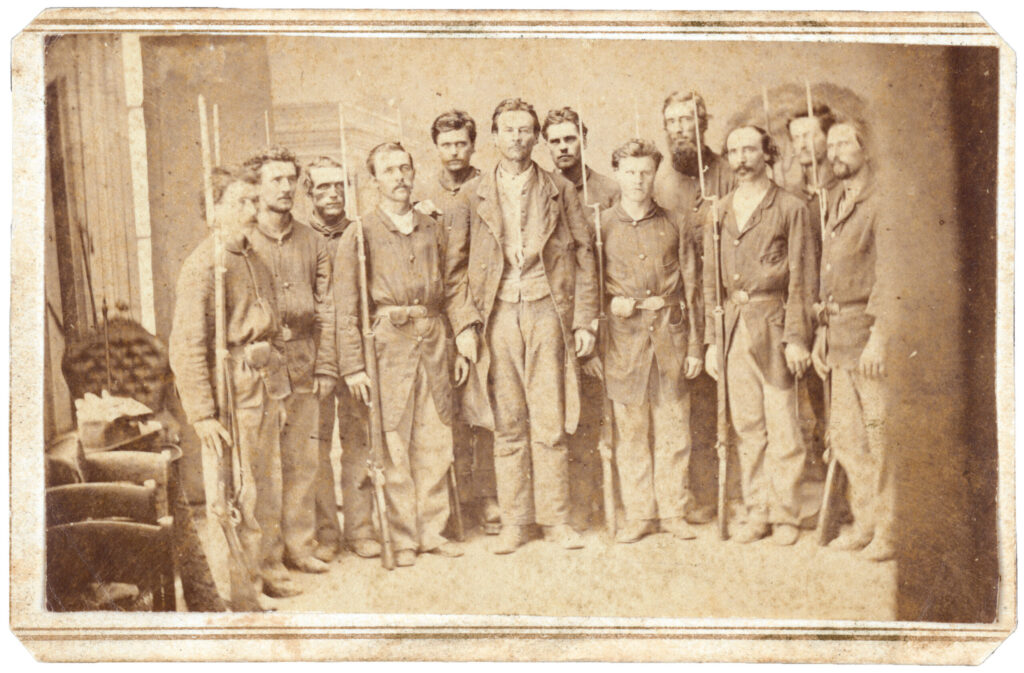

At Nashville State Prison in the fall of 1865, Ferguson posed for a photo with 11 of his guards. It reminds me of an image taken of Lee Harvey Oswald—another notorious figure in American history—while Dallas police held him in custody in 1963.

(Library of Congress)

Before his execution by hanging, Ferguson said he wanted his body sent to his family for burial in White County. “Don’t give me to the doctors,” the 43-year-old mass murderer said excitedly. “I don’t want to be cut up.”

As he is today, Ferguson was a polarizing figure in 1865. A reporter at the guerrilla’s execution questioned citizens about him.

“One man thought him a martyr, hunted down by his enemies and about to become a victim of a judicial murder,” the correspondent wrote. “Another was assured that a direr villain never went to the gallows, and declared that he ought to be hung when he was a little boy.”

Before our adventure concludes, Capps shows me the trace through the woods that he believes is the wartime road used by U.S. cavalrymen at Dug Hill. But I steer our conversation to Ferguson, who, along with Andersonville commander Henry Wirz, was one of two men hanged by the United States for war crimes committed during the Civil War.

“Do you think he got what he deserved?” I ask.

“Idda hanged him, too,” his distant relative says with a smirk.

John Banks is author of three Civil War books. His latest, A Civil War Road Trip of a Lifetime (Gettysburg Publishing), includes stories about the Battle of Dug Hill. E-mail him at jbankstx@comcast.net with your own story ideas.